Fixing Unaffordability Means Embracing Non-Market Housing

Jane Jacobs taught us to hate public housing, but the problem was how it was done, from urban design to social policy. Part two of three.

Taxing land makes sense, but how can this solve Vancouver's housing crisis?

Given the apparently inexorable increase in the asset value of land (as detailed in part one of this series), secure and decent housing seems impossibly out of reach, especially for Vancouver's working millennials.

It's time to revive a type of housing we've all but abandoned: non-market housing.

Non-market housing is not the same as social housing or public housing. Non-market housing is any housing protected from market forces, thus offering affordable rents or ownership in perpetuity. Housing co-ops, land trusts and nonprofit housing corporations are all variants of non-market housing.

But sadly, we no longer supply much in the way of non-market housing.

Why? It's partly because "public housing" — particularly the kind built in the U.S. — gave it a bad name.

Destruction in the name of urban renewal

Urban designers, architects, politicians and community activists have been highly critical of non-market housing for at least five decades.

In the U.S., public housing was virtually non-existent before the Second World War. Very poor immigrants flooded into American urban areas and found lodging wherever they could, mostly in crowded and dilapidated urban districts, forming slums.

Slums were originally called tenement districts for their many walk-up apartment buildings. These were attractive areas when they were built, but over time became the housing of last resort for the poor.

After the Second World War, public officials collectively decided that these decaying urban districts were beyond saving. For the first time, laws were passed that allowed public agencies to purchase "derelict" buildings at "fair market value" without consulting owners.

If owners argued, the courts would adjudicate their claims and, as records show, would largely side with government. Owners, often derided as "slum lords," had few defenders, so political opposition to "slum clearance" was weak.

Thousands of individual buildings were bulldozed during this era of "urban renewal," along with the tight interconnected street networks which served them.

In their place came widely spaced tower blocks in the Radiant City model. Streets were minimized to make way for pedestrianized green spaces, inspired by Le Corbusier's illustrations.

The results were disastrous. Most U.S. urban renewal public housing districts became dangerous zones that all avoided, all but those who had no other housing option. Why?

Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, had the answer. She deftly described how traditional city streets worked and why eliminating them and the buildings attached to them was such a bad idea. She used the Greenwich Village district of Manhattan as her alternative case study to prove her points. The district was very similar to those bulldozed by the champions of urban renewal.

In short, Jacobs taught us to hate public housing. But it wasn't public housing that was bad; it was the way it was done, from urban design to social policy.

Reader, a word of caution is in order before proceeding. The failures of American urban renewal were extreme.

In other countries, the results of post-war urban redevelopment efforts were not so tragic. English new towns, often antiseptic and dull to the eye, were not as dangerous. Swedish housing blocks, just as slavish to the Radiant City model as their U.S. counterparts, did not rapidly decay. Canadian public housing projects were not the tool of racial and class segregation they became in the U.S.

Architecture and urban design certainly contributed mightily to the failures of public housing projects in the U.S. But many argued rightly that the greater problem was the extent that U.S. housing projects concentrated only those who were hopelessly mired in poverty, and that this concentration of social handicaps in one place only made them more crippling.

Fuelled in part by Jacob's prescient critique, many notorious U.S. housing projects were abandoned, deemed irredeemable by virtue of their ignorant design. The most notorious example was the Pruitt Igoe housing project in St. Louis — designed by Minoru Yamasaki of Hellmuth, Yamasaki, & Leinweber, also architect of New York's World Trade Center towers — which was completed to great fanfare in 1956, only to be blown up 20 years later by the housing authority. The site still sits vacant, a symbol of both a social and urban design failure (see here).

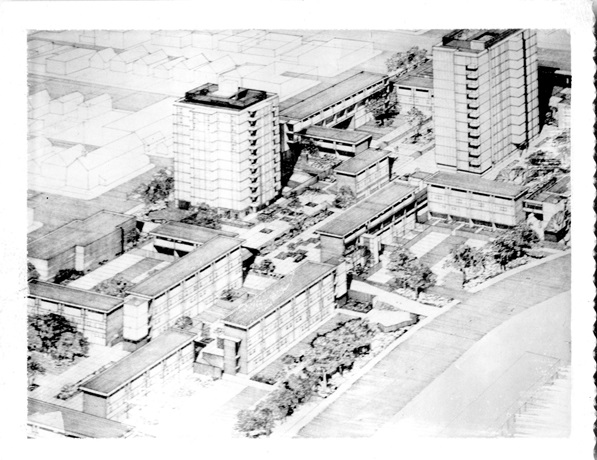

Our Vancouver example of this style housing can be seen at the Raymur Street housing project in the Strathcona neighbourhood. This large project is the only completed portion of what was to be a much larger urban renewal effort, the bulk of it never executed. Were it executed as designed, there would be nothing left of Strathcona, once considered a slum, but now one of the most desirable neighbourhoods in the city.

Slum repair?

While many people remember the housing failures, there have been numerous successful housing project rehabilitations that are less well-known.

In the 1990s, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development led an effort to correct the glaring deficiencies of Radiant City-inspired U.S. housing projects. The initiative was called Hope VI.

Some of the most poorly designed buildings, usually tower blocks, were demolished under this program. Many low-rise structures were kept, redesigning them with tweaks like private front yards and private entries protected by modest porches, making them compatible with Jane Jacob's principles so they looked like townhouses on a traditional city street. New streets were inserted across parking lots and greenswards to recreate a traditional city small block pattern.

And to overcome the stigma and ill effects of concentrated poverty, the projects required residents to be from a mix of incomes.

Consequently, many of the new rehabilitated units were to be sold. Residents would be homeowners not renters. Ironically, this successful attempt to improve public housing made it less public. By this we mean no criticism. We mean only to show that we find ourselves — planners, designers, and involved citizens — agreeing with those who argue that the only good housing is privately owned housing, be it market rental, condo or single-family house.

Market failure?

So what are we to do when the market pushes land prices out of reach for wage earners?

Is density the solution? In a previous Tyee article, co-author David Beers and I suggested a strategy called "hiving," that would allow any family making an average income or above to (just barely) afford to buy a Vancouver home.

The thinking is simple. Land costs are too high for our average wage earners. The solution is to split up the land pie. In order to make the typical single-family lot affordable, you need to cut into five or six pieces. These could be rental or strata or some combination. This may sound like a lot of density on a lot, but you can find the same density in craftsman-style homes in Vancouver's Kitsilano neighbourhood. But sadly, even with extreme effort, our computations showed that such homes would still only be affordable for those with median incomes or above. What of everyone else?

Perhaps we could wait for a global recession to bring land prices back within the reach of wage earners. To be fair, it could happen, as it did in the U.S. in 2007. But since then, land values regained lost ground and are back to what was then considered stratospheric heights.

Or we could consider accepting a difficult possibility: a healthy housing market may never come back. We haven't seen this kind of struggle for secure housing in the past 100 years. In Canada, Australia and New Zealand this past decade, average housing costs in major metropolitan areas jumped between 100 and 200 per cent!

If evidence of market failure becomes more apparent, our assumptions about the housing market must change. We must move beyond the simple reading many understood from Jacobs: public housing bad, private housing good.

In line with economist Henry George's thinking (see part one in this series), we now have a situation where the rentiers are able to extract maximum gain by acquiring, holding and collecting rents from land, up to the almost limitless point where urban crowding returns to levels not seen since the 1920s. Average rents and mortgages are beginning to consume well over half of average incomes. Developers are building increasingly smaller homes to squeeze as much as possible out of the land. The housing situation for millennials today is nothing like what their parents had to face.

In such times, ideas that were once the ravings of radicals are now both practical and necessary. To house wage earners we must, as Henry George would suggest, tax land — both to reduce speculative pressures and to supply the funds necessary to build non-market housing for the disappearing middle class.

Happily there is a precedent for this. It is Vienna, where for exactly 100 years they have taxed land to build housing. Sixty per cent of Vienna residents now live securely in non-market housing. We examine their model in the third and final part of this series here. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

No comments:

Post a Comment